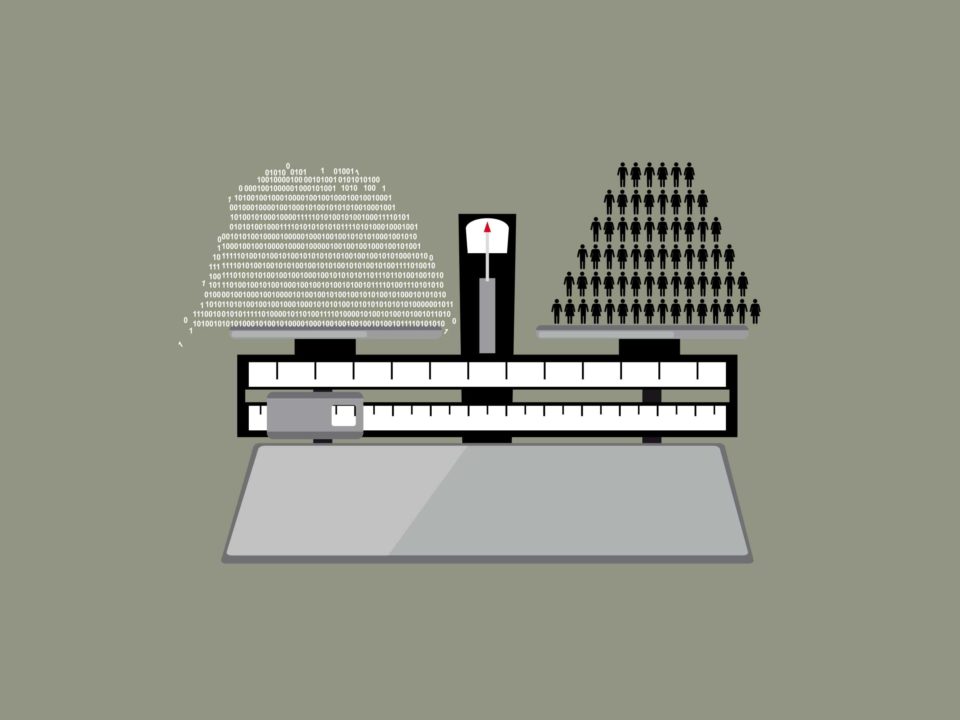

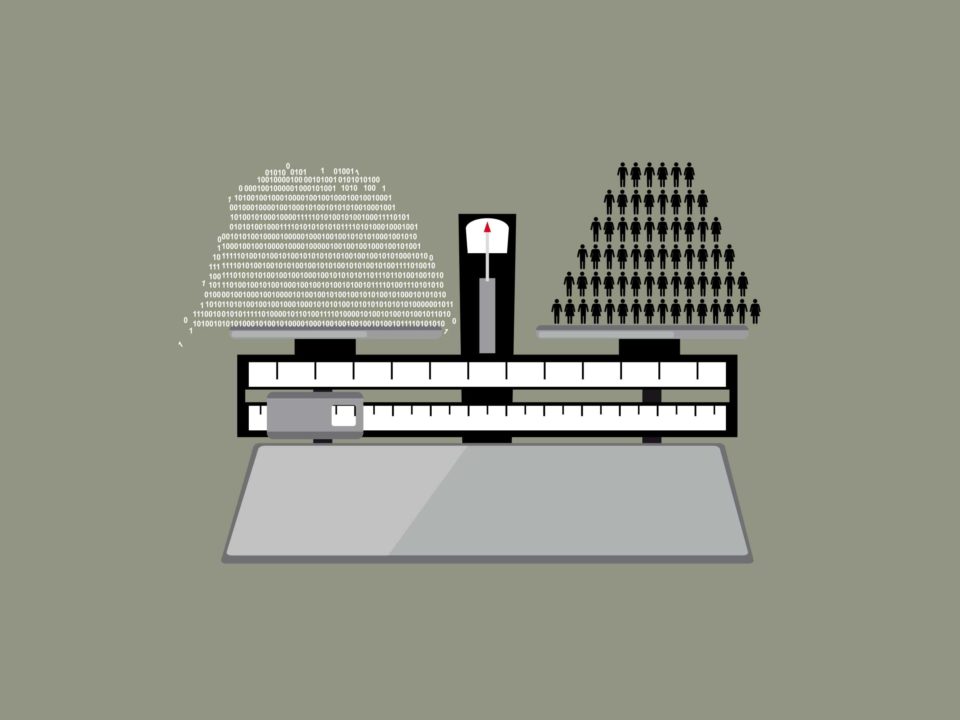

We are in the midst of an unprecedented surge of investment into artificial intelligence (AI) research and applications. Within that, discussions about ‘ethics’ are taking centre stage to offset some of the potentially negative impacts of AI on society.

copyright by blogs.lse.ac.uk

In June 2018, the Mayor of London released a new report that identifies London’s ‘unique strengths as a global hub of Artificial Intelligence’ and positions the capital as ‘The AI Growth Capital of Europe’. This plea coincides with the government’s focus on ‘ AI & Data Economy ’ as the first out of four ‘Grand Challenges’ to put the UK ‘at the forefront of the industries of the future’. The AI Sector Deal of £1 billion, part of the Industrial Strategy, has seen private investment of £300 million, alongside £300 million government funding for research in addition to already committed funds.

In June 2018, the Mayor of London released a new report that identifies London’s ‘unique strengths as a global hub of Artificial Intelligence’ and positions the capital as ‘The AI Growth Capital of Europe’. This plea coincides with the government’s focus on ‘ AI & Data Economy ’ as the first out of four ‘Grand Challenges’ to put the UK ‘at the forefront of the industries of the future’. The AI Sector Deal of £1 billion, part of the Industrial Strategy, has seen private investment of £300 million, alongside £300 million government funding for research in addition to already committed funds.

Albeit significant, these investments are small compared to, for example, France’s pledge of €1.5 billion pure government funding for AI until 2022 or Germany’s new ‘Cyber Valley’ receiving over €50 million from the state of Baden-Württemberg alone in addition to significant investments from companies such as Bosch, BMW, and Facebook. The EU Commission has pledged an investment into AI of €1.5 billion for the period 2018-2020 under Horizon 2020, expected to trigger an additional €2.5 billion of funding from existing public-private partnerships and eventually leading to an overall investment of at least €20 billion until 2020. This wave of AI funding is, in part, a reaction to the Silicon Valley’s traditional domination of the AI industry as well as China’s aspiration to lead the field (focused on both soft- and hardware and comprised of large-scale governmental initiatives and significant private investments).

Large-scale investments to boost (cross-)national competitiveness in emerging fields are hardly new. What is special about this surge of investment into AI is a central concern for ethical and social issues. In the UK, the AI Sector Deal entails a new Centre for Data Ethics whilst a recent report by the House of Lords Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence puts ethics front and centre for successful AI innovation in the UK. Relatedly, London-based AI heavyweight DeepMind launched its Ethics and Society research unit in late 2017 to focus on applied ethics within AI innovation, alongside a range of UK institutions embarking on similar missions (such as The Turing Institute with their Data Ethics Group).

The UK is not alone in the race for ‘ethical AI’: the ‘Ethics of AI’ are a central element of France’s AI strategy; Germany released a report containing ethical rules for automated driving in 2017; Italy’s Agenzia per l’Italia Digitale published a White Paper on AI naming ‘ethics’ as No.1 challenge; the European Commission has held the high-level hearing ‘A European Union Strategy for Artificial Intelligence’ in March 2018 and recently announced the members of its new High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, tasked with, among other things, drafting AI ethics guidelines for the EU Commission. A similar picture materialises outside Europe – in Canada, America, as well as in Singapore, India and China as well.

With these kinds of issues surfacing, specific concerns that cut across the international AI landscape are materialising. To address these, different strategies are being suggested such as implementing re-training schemes for workers, algorithm auditing, re-framing the legal basis for AI in the context of human rights (including children’s rights in the digital age), calling for AI intelligibility, voicing concerns against AI privatisation and monopolisation, suggesting ‘human-centred AI’, proposing an AI citizen jury and calling for stronger and more coherent regulation. […]

read more – copyright by blogs.lse.ac.uk

We are in the midst of an unprecedented surge of investment into artificial intelligence (AI) research and applications. Within that, discussions about ‘ethics’ are taking centre stage to offset some of the potentially negative impacts of AI on society.

copyright by blogs.lse.ac.uk

Albeit significant, these investments are small compared to, for example, France’s pledge of €1.5 billion pure government funding for AI until 2022 or Germany’s new ‘Cyber Valley’ receiving over €50 million from the state of Baden-Württemberg alone in addition to significant investments from companies such as Bosch, BMW, and Facebook. The EU Commission has pledged an investment into AI of €1.5 billion for the period 2018-2020 under Horizon 2020, expected to trigger an additional €2.5 billion of funding from existing public-private partnerships and eventually leading to an overall investment of at least €20 billion until 2020. This wave of AI funding is, in part, a reaction to the Silicon Valley’s traditional domination of the AI industry as well as China’s aspiration to lead the field (focused on both soft- and hardware and comprised of large-scale governmental initiatives and significant private investments).

Large-scale investments to boost (cross-)national competitiveness in emerging fields are hardly new. What is special about this surge of investment into AI is a central concern for ethical and social issues. In the UK, the AI Sector Deal entails a new Centre for Data Ethics whilst a recent report by the House of Lords Select Committee on Artificial Intelligence puts ethics front and centre for successful AI innovation in the UK. Relatedly, London-based AI heavyweight DeepMind launched its Ethics and Society research unit in late 2017 to focus on applied ethics within AI innovation, alongside a range of UK institutions embarking on similar missions (such as The Turing Institute with their Data Ethics Group).

The UK is not alone in the race for ‘ethical AI’: the ‘Ethics of AI’ are a central element of France’s AI strategy; Germany released a report containing ethical rules for automated driving in 2017; Italy’s Agenzia per l’Italia Digitale published a White Paper on AI naming ‘ethics’ as No.1 challenge; the European Commission has held the high-level hearing ‘A European Union Strategy for Artificial Intelligence’ in March 2018 and recently announced the members of its new High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, tasked with, among other things, drafting AI ethics guidelines for the EU Commission. A similar picture materialises outside Europe – in Canada, America, as well as in Singapore, India and China as well.

With these kinds of issues surfacing, specific concerns that cut across the international AI landscape are materialising. To address these, different strategies are being suggested such as implementing re-training schemes for workers, algorithm auditing, re-framing the legal basis for AI in the context of human rights (including children’s rights in the digital age), calling for AI intelligibility, voicing concerns against AI privatisation and monopolisation, suggesting ‘human-centred AI’, proposing an AI citizen jury and calling for stronger and more coherent regulation. […]

read more – copyright by blogs.lse.ac.uk

Share this: